"Ter medo do futuro se transformou em algo comum e a necessidade de reverter o cancelamento do futuro se transformou em tarefa de parte significativa da sociedade" (Estudo de Cena).

"O medo do futuro se alastra, a necessidade de arrancar alegria ao futuro nos atravessa" (Notas para a vida no LIMIAR).

In the "Prólogo Documental" of Notas para a vida no LIMIAR (2022), the actors make a series of statements about our current situation:

"Diante dos nossos olhos se aprofundam crises financeiras, ecológicas, viróticas, socias. Paira no presente uma sensação, difusa, de uma crise profunda e ampla."

"Vivemos dentro de um cadáver chamado Capitalismo, que se move sugando nossas vidas, nosso passado, nossas palavras."

And finally: "Estamos no limiar: ou vamos superar nosso modo de vida ou o exterminismo do presente já é o nosso futuro."

Our fear of the future comes from a strong feeling -- a certainty, almost -- that we won't overcome our mode of life and that the exterminism of the present already is our future.

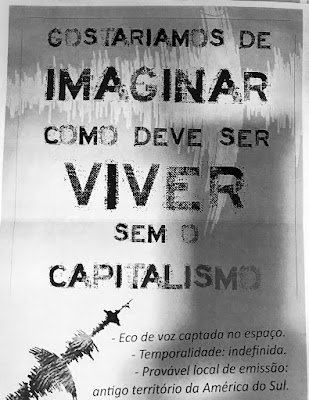

Notas para a vida no LIMIAR takes place in a dystopian future that is not so distant nor so different from our present. After seeing the piece, an audience member commented that if this is what "viver sem o capitalismo" looks like, he'd rather continue to live inside this life-sucking "cadáver." What he didn't consider is that the dystopian future of the play is not a future "sem o capitalismo" but with it. If this future feels like "o fim do mundo," it's not because capitalism has come to an end but because it hasn't.

But there are other, more hopeful glimpses of the future. For instance, we hear of a anti-capitalist "comunidade" that has disappeared in the year 2058, whose insurrectionary "ditado popular" was, "Não precisamos salvar o capitalismo, precisamos nos salvar dele."

We also hear of the "revolta de 2062," in which a woman rebel "enforcou um soldado com a alça de sua blusa."

We don't know what happens after this revolt of 2062, but it may be the start of a series of uprisings that eventually leads to the Revolução Popular about which we hear in Utopia da Memória (2019), the group's previous work. There, someone from the future recalls "janeiro de 2119, quando a gente comemorou nas ruas os primeiros 100 dias da Revolução Popular."

In a letter dated "2134, ano 15 da Revolução Popular," we learn that a lot of things we think can't be abolished -- "As cercas, os latifúndios, as muralhas, as propriedades, as fortunas, o dinheiro" -- "não existem mais." Perhaps most significantly, we learn that "hoje . . . quando vamos dormir não tememos o amanhã."

In Pedagogia da indignação (2000), Freire wrote that "uma das bonitezas do anúncio profético está em que não anuncia o que virá necessariamente, mas o que pode vir, ou não. O seu não é um anúncio fatalista ou determinista. Na real profecia, o futuro não é inexorável, é problemático. Há diferentes possibilidades de futuro."

To me, the act of imagining the Revolução Popular of 2118 is an example of prophetic-utopian annunciation. It's not that this will necessarily happen, but that it could -- and this is the point. "A realidade está grávida de possibilidades," we hear in the prologue of Notas para a vida no LIMIAR, which is to say it is open to "the possibility -- though not the inevitability -- of catastrophes on the one hand and great emancipatory movements on the other" (Löwy, Fire Alarm 110).

The anunciation of instances of uprising like the revolt of 2062 and the Revolução Popular of 2118 is not meant to foretell but to "tencionar o futuro," opening it up to alternatives -- "ou vamos superar nosso modo de vida ou o exterminismo do presente já é o nosso futuro."

"Utopianism is the general label for a number of different ways of dreaming or thinking about, describing or attempting to create a better society" (REP).

In Utopia da Memória and Notas para a vida no LIMIAR, utopianism is a way of dreaming about "o fim do capitalismo" so as to "reverter o cancelamento do futuro," and, what's more, "arrancar alegria ao futuro" by infusing it with the possibility of a life without capitalism.